Antiabortion movement defends Comstock laws

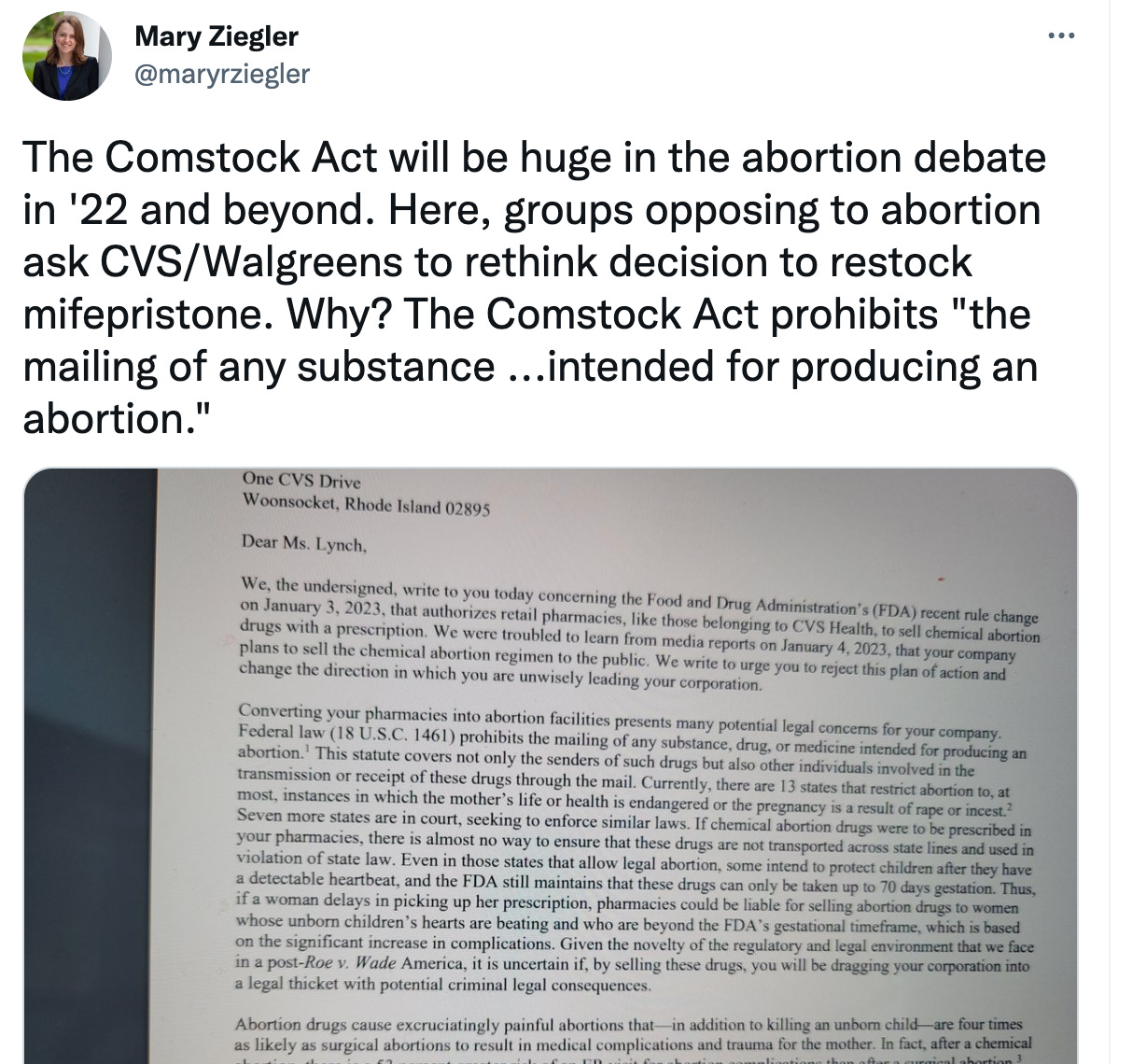

Dr. Mary Ziegler points out how Comstock precedent was cited in letter to CVS

Antiabortion advocates have sent letters to major pharmaceutical companies asking them to not send abortion pills in the mail because it would violate the Comstock Act.

That reporting was revealed on the Twitter feed of Dr. Mary Ziegler, a leading abortion rights scholar and author of a forthcoming book detailing the history of the issue. Comstock laws were puritanical regulations of sexual-based literature and contraceptives–along with abortion–that passed in the 19th century.

Anthony Comstock, a bald man with a horseshoe mustache, served in the infantry during the Civil War before moving to New York City, which teemed with prostitutes and obscene publications. In the late 1860s, he personally investigated and then told police about vice. In 1872, he got Congress to pass the Comstock Act, which defined contraceptives as obscene, as well as information on it and abortions. Comstock’s clout derived from his role as the leader of the New York Society for the Suppression of Vice, which was a heavily influential organization in the Victorian era. The Act made it a federal crime to disseminate birth control through the mail or across state lines.

Much of Margaret Sanger’s early battles for birth control dealt with flouting Comstock laws. Sanger wrote a pamphlet titled Facts on Abortion and Legislation in Relation to Birth Control in 1921. She said birth control laws–or those put forth by Comstock or other state lawmakers–repressed women.

Mary Coffin Ware Dennett, a suffragette originally from Worcester, Massachusetts, also advocated the repeal of Comstock Laws. She published a sex education pamphlet that soon became popular, called “The Sex Side of Life: An Explanation for Young People.” It featured diagrams, proper medical terminology, and explanations of the impacts of sex, both physiologically and emotionally. Dennett had created it for her 14-year-old son about sex because she found most educational materials about sex to be inadequate and shaming.

Most had been filled with euphemisms and unclear explanations because of how obscene it had been to talk about sex at the time. Her work was published in the Medical Review of Reviews in 1918. Dennett then published the pamphlet to a wide audience. The YMCA distributed it and it was used in public schools and at Union Theological Seminary, one of the most prominent Protestant seminaries in the U.S. Between 1918 and 1928, more than 35,000 copies were sold to a variety of people and institutions.

By 1922, the U.S. Post Office declared the pamphlet obscene and un-mailable. Later a postal office employee entrapped Dennett when he requested a pamphlet. She was charged with violating the Comstock Act. The trial featured puritanical testimony on behalf of the government and scientific-based arguments for the defense. A jury convicted her and she was fined $300.

The case dominated headlines across the nation. Generally, editorials saw the laws as archaic and unscientific. Eventually, the verdict was overturned by Augustus Noble Hand, a well-known and respected liberal jurist, who said that material must be reviewed as a whole instead of in parts when judging its obscenity.

That’s just a little historical refresher for people who needed to be reminded of what the Comstock laws were or how they were central to the beginning of the reproductive rights movement.