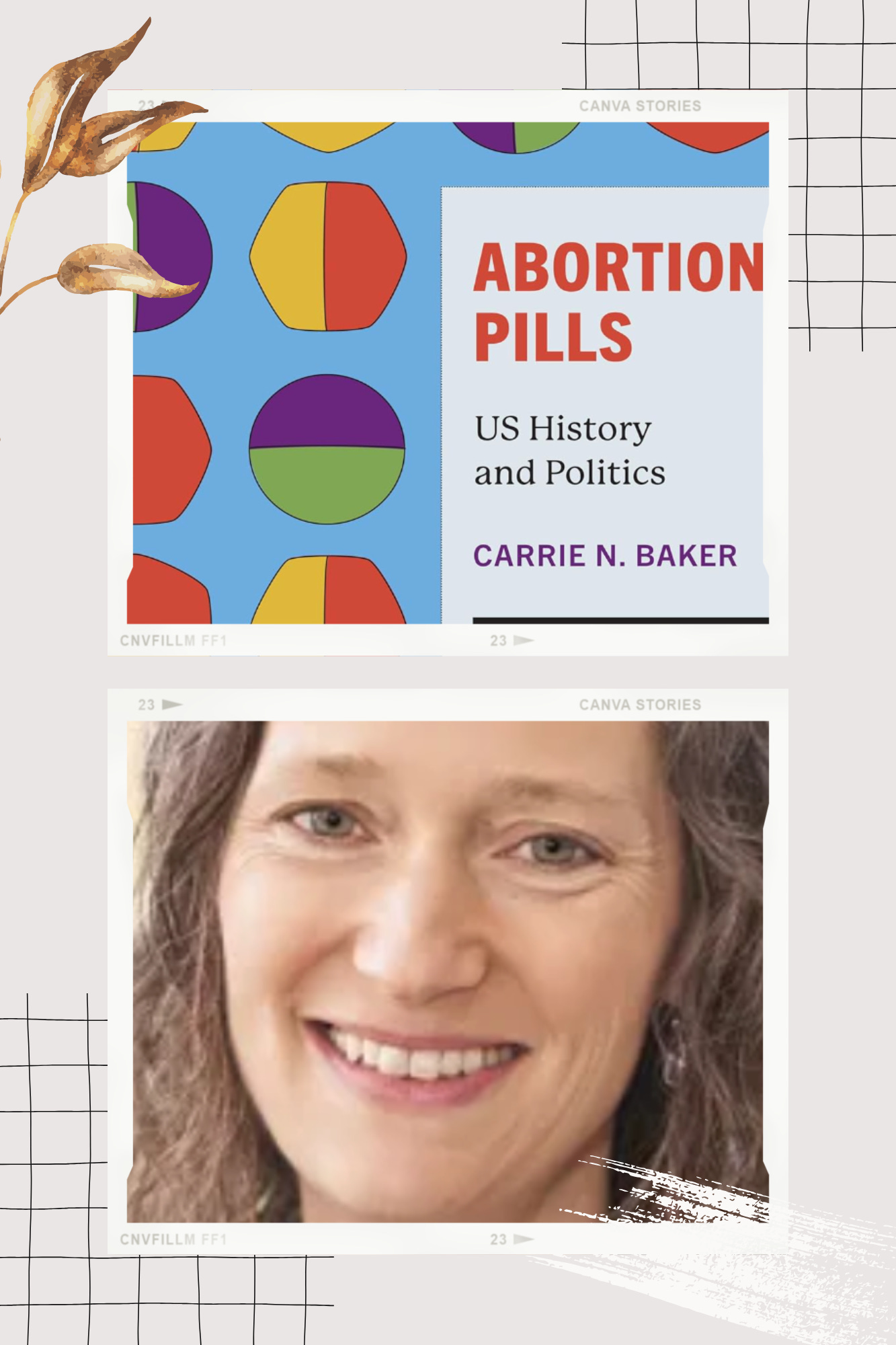

New book provides definitive account of medication abortion

Professor Carrie N. Baker undertook project to give an accurate and comprehensive history of mifepristone.

A new book provides a definitive account of how medication abortion came to be, along with a detailed look at the challenges its providers now face.

Abortion Pills: US History and Politics was written by Carrie N. Baker, the chair of the Program for the Study of Women and Gender at Smith College. Of all the books I read last year about abortion, this work most deeply impressed me. It taught me things that I hadn’t known about its history, and I’ve read hundreds of texts and written a comprehensive book on the topic.

“With all this misinformation about the history of what actually happened, I wanted a real history to be out there that could be cited by folks defending mifepristone,” Baker said.

The story begins decades ago with a French researcher who is known as the Father of the Abortion Pill.

Étienne-Émile Baulieu had conducted research with people who had developed the birth control pill. During that time, he and others envisioned using progesterone to cause a pregnancy to end. He was contracted to work with Roussel Uclaf, a pharmaceutical company in France. That work eventually led to the development of RU-486, which is now known as mifepristone. It was finished by 1980, but it took eight tumultuous years in Europe to get approved for widespread use.

When it finally was, the news was met with hostility from the Catholic Church.

“This was a time also when these extremist Catholics were bombing,” Baker said. “They bombed a movie theater, and they bombed another location. So, it was sort of a harbinger of what was going to happen in the future in the United States.”

That danger also hampered its approval in the United States. The 1980s were riven by antiabortion violence. Terrorists bombed clinics and even kidnapped a doctor and his wife. George H.W. Bush, elected president in 1988, put an import ban on RU-486.

That’s when a major feminist campaign led by an organization called the Population Council pushed for its approval and acceptance as a treatment option for women who wanted an abortion. The text spends most of its time discussing how key figures like Eleanor Smeal, Lawrence Lader, and Beverly Winikoff worked in tandem to eventually get it approved for the public more than a decade later.

It’s fascinating to see how one leader operates when it conflicts with how another works. The abortion rights movement has a lot of influential personalities that are as assertive as can be. That creates an argumentative environment. Regardless, the result was productive, and American healthcare improved. One point of contention among abortion rights activists was whether it would harm brick-and-mortar clinics.

“There was a lot of division in the feminist movement about this new technology,” Baker said.

That’s still something people argue about when discussing whether telehealth options should be expanded. Many doctors, including some I’ve spoken to, said that surgical abortion can only remain an option if people continue to patronize the clinic, even with medication as their choice.

The Food and Drug Administration's operation was detailed later in the book. To say it took a conservative approach is an understatement. Many of the early precautions taken with the drug were more rigid than needed, given how safe it proved to be. Some feminist activists had hoped that it would make abortion more accessible.

“It really hasn't been until recently that access to this medication has been significantly expanded because of recent phenomena,” Baker said. “And even today, it's still restricted more than it should be.”

The challenges that the COVID-19 pandemic presented and how it forced abortion providers to adapt by using telehealth is a large part of the latter part of the book. That presented problems when some women used abortion medication later in pregnancy than they expected. That even led to one Texas woman, Lizelle Herrera, being prosecuted for murder.