UK Group counter protests antiabortion march

England currently has a law in place that calls for life imprisonment for certain instances of abortion. Several women have been charged in the last few years.

At the annual March for Life in London over the weekend, pro-choice activists organized a counter rally full of speakers from there and abroad who discussed the importance of reforming laws in Parliament so that reproductive rights are protected.

In the country, there have been six prosecutions of women who took abortion medication. Abortion clinics there communicated with activist leaders and told them that they had been contacted more than 100 times as police investigated women for violating the Offense Against the Person Act, a Victorian-era law passed in 1861 that calls for nearly life imprisonment for performing an abortion.

Kerry Abel, one of the counter-protest organizers, spoke to me about what’s going on there and what compelled them to act.

“They're taking people who aren't organized, who don't have a lot of resources or legal coordination through the courts,” Abel said. “We don't think it's in the public interest. And we think it's really bad to prosecute women who are just trying to deal with the situation they were faced with at the time.”

One Englishwoman was convicted and sentenced to 18 months in prison for criminal abortion. She had her sentence commuted, but she served time, which is the more important point.

The law had historically targeted people who performed the abortion and not the women who received it. But as it is unclear who is responsible for doing it, the women who took the pill are the ones held accountable for terminating a pregnancy.

What may surprise some American reproductive rights scholars and leaders is that the laws in Europe are not as liberal as much of the United States. In states like New York or Pennsylvania, or elsewhere with legal abortion, a woman can go into a clinic and get an abortion with no questions asked. In England, a woman has to go to a doctor and demonstrate that she would have mental distress if she carried on with a pregnancy. She is then given permission, which, in most cases, is granted.

Virtually all English women ever prosecuted for criminal abortion have been charged within the last six years–as telehealth and the popularization of abortion medication as an option.

A little history is helpful. It wasn’t until the 1930s, with the formation of the Abortion Law Reform Association, that feminists and doctors began pushing for liberalization of the laws. At the time, some, like British birth control pioneer Marie Stopes–who is to England what Margaret Sanger is to America–hadn’t wanted to focus on abortion. But pioneering feminists like Stella Browne and Janet Chance did.

They brought the issue to national attention in 1938 with the case of Rex v. Bourne.

Dr. Aleck Bourne, an OB/GYN, performed an abortion on a 14-year-old rape victim. It arose from the brutal sexual assault of Nellie Hales, who lived in London with her parents, Horace, and her mother, who was also named Nellie. Three royal guardsmen at the Horse Guards in London lured her into a stall where they raped her repeatedly. Afterward, her mother took her to a Catholic hospital where a doctor told them that he wouldn’t perform an abortion because the baby could be a future prime minister. English law called for adoption in situations where rape led to pregnancy.

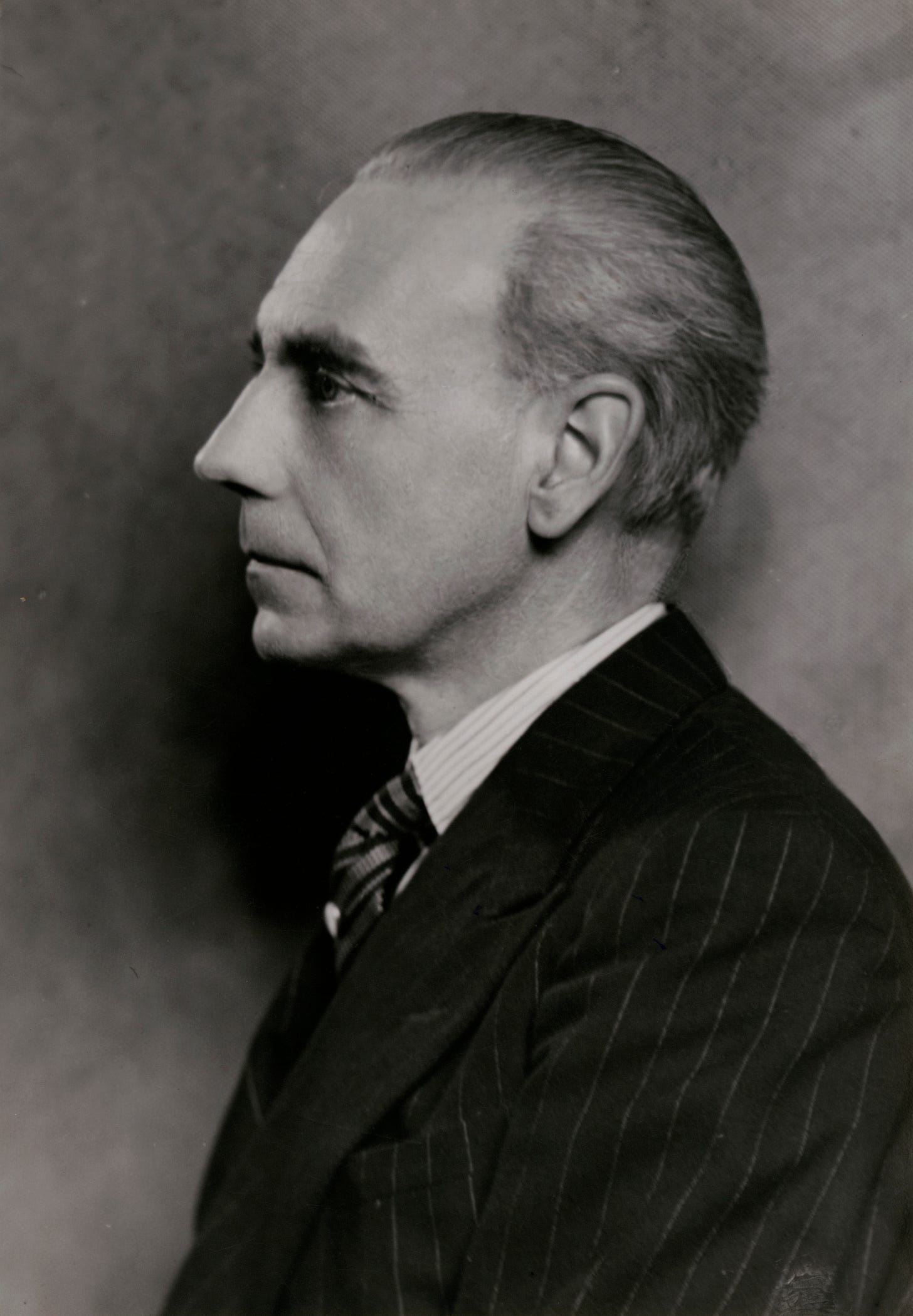

(Aleck Bourne)

Later, the mother wrote a letter to Joan Malleson, who worked at St. Mary’s Hospital and was a member of the Abortion Law Reform Association. In turn, she contacted Bourne, who agreed to perform an abortion. When I spoke to Bourne’s grandson, he told me that his grandfather had wanted to take the abortion business away from midwives. The association wanted a sympathetic test case. It went before a jury at Old Bailey, the most famous courthouse in the world. The jury acquitted him on the same day it deliberated.

That galvanized the abortion rights movement all over the world. And it’s what eventually led to the 1967 liberalization in England. The 1967 reforms led to English law permitting abortions when a continued pregnancy will cause significant harm to a woman’s well-being. It also can’t be past the 24th week.

I traveled to England to research the Bourne abortion case for my book, as well as a play and screenplay that I am penning. I hope to have that staged in America or England, or both. It’s a timely story that has never been dramatized in a theatrical or cinematic work.

Important things to note about the reforms that came in the 1960s. They stipulated that the abortions had to be done in hospital settings or approved medical clinics. The design of that law was to ensure that women were getting the safest possible care and not entering dangerous back alley environments. It wasn’t designed with abortion medication in mind, much like the Supreme Court precedence after Roe.

At the March for Life parade held the same day, thousands of people marched past Parliament and then took to the square to listen to religious music. Much of the antiabortion movement there is funded by American organizations. The UK branch of the US-based right-wing lobby group, Alliance Defending Freedom, which wants abortion to be banned, has more than doubled its spending since 2020. This year, they reportedly spent almost £1 million to influence UK MPs ahead of a historic vote on abortion law reform.

The unclear way in which authorities should handle abortion is something activists hope to have addressed within the next year. Before the march on Saturday, I met with Louise McCudden, UK head of external affairs at MSI Reproductive Choices, an abortion provider there. She told me that there were 335 new members of Parliament this year, and more than 40 percent of them were women.

“We encourage all MPs, regardless of when they were elected or what party they represent, to engage with abortion providers, Royal Colleges, and healthcare policy experts on reproductive choice,” McCudden said. “As a leading abortion provider, our door is always open to any policymakers who want to understand abortion and ask open, honest questions.”