Universal daycare: Is it something that could happen now?

Movement for 24-hour publicly funded service started in second wave

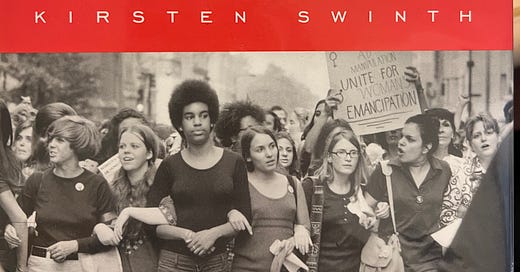

(The cover of Dr. Kirsten Swinth’s book about early feminist struggles for equality in work and at home)

With contemporary feminists popularizing reproductive justice philosophy, it’s worth looking back on the time when women and men fought for universal 24-hour daycare.

Reproductive justice philosophy is based on the principle that abortion rights are just as important as the government supporting women who wanted to have children. The movement for that developed because of a collection of women of color who discussed the topics between 1989 and 1994. They pushed for greater acceptance of anti-poverty initiatives within the reproductive rights movement. Loretta Ross and Dazon Dixon Diallo–among others–were key figures in its rise.

But when examining feminist history, the desire to advance welfare and daycare rights came earlier. In Dr. Kirsten Swinth’s book, Feminism’s Forgotten Fight: The Unfinished Struggle for Work and Family, she explained the devastating loss that came with their effort to make that a basic service of the federal government.

“This is one of those core heartbreaking moments in feminist history,” Swinth said over the phone. “It did receive popular attention. There was legislation that was passed by Congress in 1971 for comprehensive childcare at the national level. And President Nixon unexpectedly vetoed it.”

The National Organization for Women placed universal childcare as a public entitlement in its Bill of Rights that it published at its 1967 convention.

The emerging conservative opposition to feminism, led by Phyllis Schlafly, argued that a woman’s role was in the home. They were meant to be someone who supported their husbands by taking care of children.

It’s important to note that feminists wanted 24-hour daycare for reasons beyond the supervision of children while women went to work. The service could free up the time for many things–exercise, socializing and public service among them.

“They don't think childcare (was there) so women can go to work,” Swinth said. “That equivalence just wasn't part of the story. There was just a much more comprehensive and holistic sense of the value of universal childcare.”

Swinth described the early movement In the book’s chapter that explains the childcare movement of the 1970s. There had been an underground service that women could take their children to in New York’s Lower East Side. It was known as Liberation Nursery, and in many ways it was unhygienic. Other cities also violated laws regulating the business.

The movement culminated in the Comprehensive Child Development Act, which was introduced in Congress in 1970. When it reached Nixon’s desk in December 1971, he vetoed the bill after he was deluged with letters saying it was an invasion of the family.

With roles changing for household partnerships, modern feminists may be wise to reevaluate whether this is something that could become a reality. The failures of the past may make leaders and grassroots activists reluctant to place such an emphasis on it. But Swinth thinks it’s a cause that could galvanize women if people felt invested in it.

“I remain optimistic. I remain hopeful,” Swinth said. “I think it's an urgent need, and something we should pursue. Do I think in this political atmosphere that we are in today (that we could get) government-funded universal programs? Would we have the political support it needs to pass Congress and (get to) the president? No. I think we still have a big fight ahead of us for that to be the case.”