Who was Anthony Comstock?

Author Amy Werbel researched a book on puritanical man whose work has now been used for antiabortion arguments

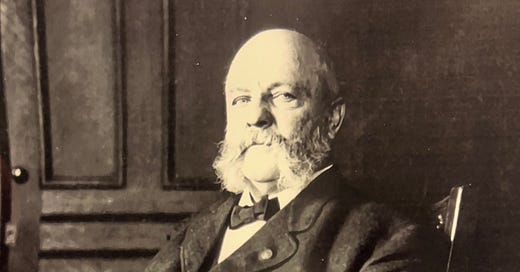

(Anthony Comstock, a 19th-century puritanical reformer who went after people who mailed abortifacients and contraceptives)

Supreme Court Justice Clarence Thomas quizzed the lawyer for a drug manufacturer of mifepristone during a recent case about whether the Comstock Act–a 19th-century law that forbids the mailing of abortifacients and contraceptives–legally prevents them from distributing it now.

But what exactly is the Comstock Act? And why is it something that now may be the basis for a precedent that forbids the mailing of abortion medication?

I wanted to answer those questions when I spoke to Dr. Amy Werbel, author of Lust on Trial: Censorship and the Rise of American Obscenity in the Age of Anthony Comstock.

“It's an example of opportunistic originalism, as people like to call it,” Werbel said. “That you could somehow stick to the way things were imagined at the time that they were passed, and just think, here's a tool for what it’ll accomplish, which is to limit women's access to reproductive care and family planning.”

Anthony Comstock was a puritanical reformer who targeted obscene literature and abortionists during his time. He was the antagonist of Madame Restell, who committed suicide during a trial of her that had been a result of Comstock leading a crusade against the famous New York abortionist. Comstock created the New York Society for the Suppression of Vice, which was given quasi-police powers to investigate people who distributed obscene materials. They also went after those who mailed contraceptives.

Congress enacted the Comstock Act in 1873, an amendment to the postal code that forbids the mailing of abortifacients. Comstock was appointed as an inspector for the Post Office. He pursued many people who violated the laws after being tipped off by people who had sought to catch those who violated them.

It wasn’t until Margaret Sanger and her husband, William Sanger, began the modern birth control movement that these laws were challenged and struck down eventually through decades of advocacy on their part and through legal challenges.

One of the landmark cases was United States v. One Package of Japanese Pessaries. Dr. Sakae Koyoma of Osaka, Japan, had sent a pessary, or diaphragm, to Sanger to test it on women at her clinic. Customs officials seized it.

The case was heard by District Court Judge Grover Muscowitz, who said that the intention of the doctor mattered, and he gave leeway in permitting the use of the contraceptive for reasons beyond preventing pregnancy.

The government appealed. Sanger’s lawyer, Morris Ernst, enlisted the help of Harriet Pilpel, one of his female associates. Pilpel became one of the most influential lawyers in the birth control movement’s history as she progressed under Ernst’s mentorship.

The case was heard by a three-judge panel of the Court of Appeals, which featured Learned Hand, Augustus Hand–they were cousins–and Thomas Swan. The appellate court upheld the ruling. Ernst and Pilpel called Augustus Hand's ruling the “Bill of Rights” of birth control.

The Attorney General did not further appeal. Subsequently, the customs office issued a memo stating that imported contraceptive devices would not be detained if the consignee was a reputable physician seeking to protect his or her patient’s health.

The decision effectively meant that birth control could be prescribed and distributed in all instances where doctors thought a pregnancy would harm the woman’s health. Public opinion polling indicated that most Americans felt birth control should be legal and accessible to married couples.

The Supreme Court eventually established a right to birth control in Griswold v. Connecticut, and a few years later, they established abortion rights as protected by the Constitution in Roe v. Wade. Since abortion medication wasn’t even an option then, it wasn’t a question that legal scholars or the justices considered. But the decisions made the Comstock laws moot anyway.

Yet the laws were never repealed by Congress. And much like the Arizona decision to permit the 1864 ban to go into effect, there is a legal argument spreading that this law has come back into effect since it was never struck down or repealed.

“It just seemed unimaginable that this person would have currency in modern American society,” Werbel said. “But then, of course, here we are.”